N’tomo masks

Mali, Bamana

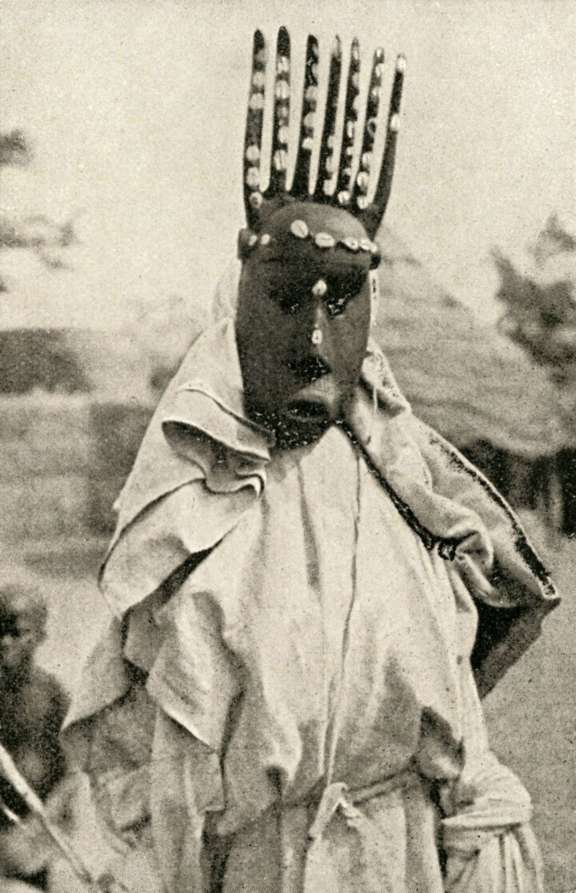

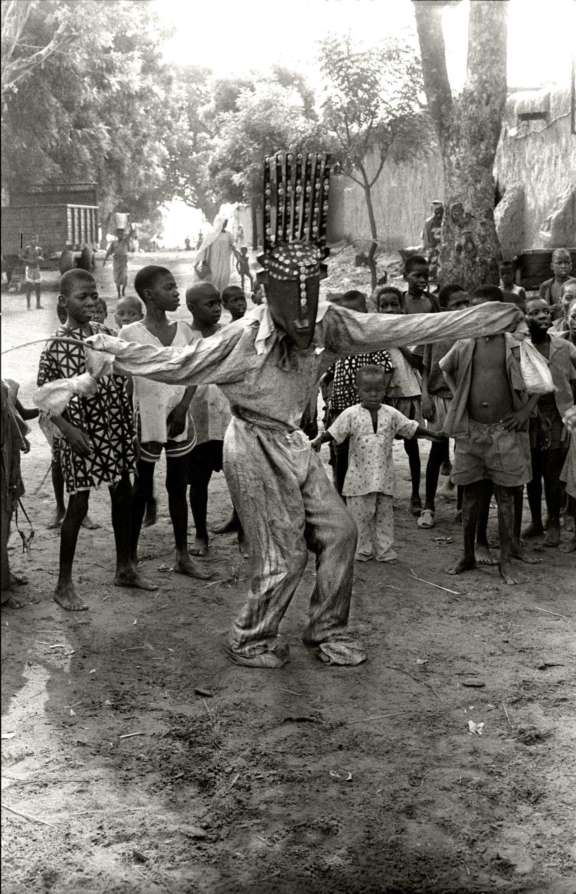

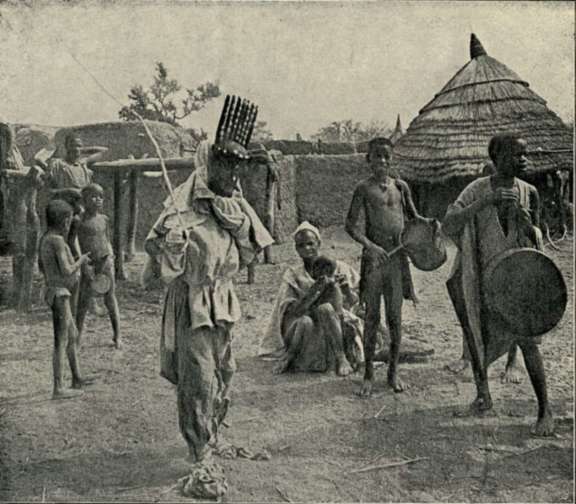

N’tomo face masks are usually surmounted by three to eight horns forming a comb, and are associated with a stage in the compulsory education of uncircumcised boys in certain West African societies. The unobtrusiveness or even absence of the mask’s mouth, stresses the behaviour expected in their future adult life at the end of the training: controlling and weighing one’s words, knowing how to remain silent, safeguarding secrets and bearing pain in silence.

Aura 22 N’tomo Mask

-

Bamana people

- Mali

- 19

th century - Wood, metal, cotton and glass beads

- H 50 cm; W 16 cm; D 20 cm.

Origin

- Former René Rasmussen collection, Paris

- Former Simone de Monbrison collection, Paris, 1968

- Galerie Alain de Monbrison, Paris

- Former Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière collection

- Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac (70.2017.66.18), Gift Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière.

Aura 14 N’tomo Mask

-

Bamana people

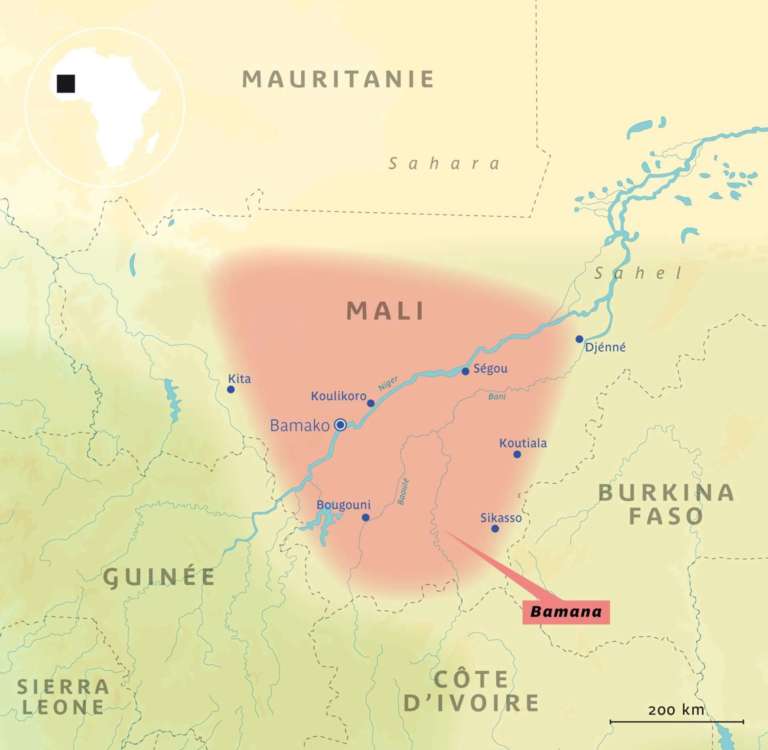

- Mali, workshop in the Ségou region

- Wood and glass beads

- H 64 cm; W 21 cm; D 16 cm.

Origin

- Former Georges Frederick Keller collection (1899-1981), Paris (inv. G.F.K. 13)

- Former Paolo Morigi collection, Lugano, 1981-2005

- Sotheby’s, Paris, Paolo Morigi collection, 6 December 2005, lot no. 29

- Former Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière collection, Paris

- Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac (70.2017.66.10), Gift Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière.

The work’s original context

N’tomo: from Bambara to Bamana

N’tomo face masks are usually surmounted by three to eight horns forming a comb, and are associated with a stage in the compulsory education of uncircumcised boys in certain West African societies. The unobtrusiveness or even absence of the mask’s mouth, stresses the behaviour expected in their future adult life at the end of the training: controlling and weighing one’s words, knowing how to remain silent, safeguarding secrets and bearing pain in silence.

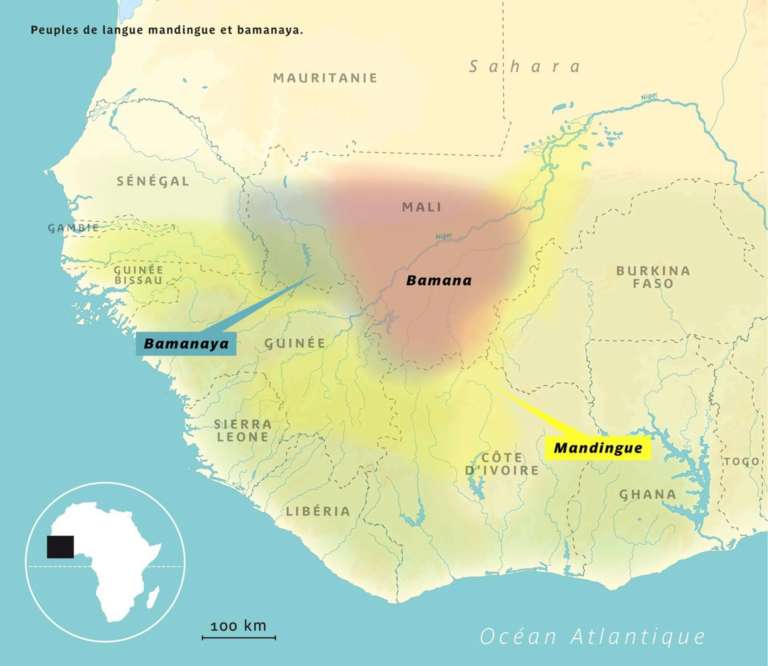

This school, known as N’tomo, was once widespread in an area that fluctuated in the course of history, corresponding to a large part of Mali, north-eastern Guinea and Northern Côte d'Ivoire, a territory in which a common art of living was shared: the bamanaya1. It was shaped over almost two millennia with contacts between West Africa’s political entities, from the Sahel to the wooded savannah. These Mande-speaking populations, subjects of the Ghana Empire (3rd-12th century) and then of the Mali Empire in the 13th century, built a culture with “certain religious practices, a way of explaining the world and a mode of action through rituals in a search for happiness (here)”2.

The region’s Muslim merchants used the term “bambara”, which means “infidel”, to refer to the non-Muslim peoples of a territory with vague boundaries, including the Mande region and even beyond. Europeans adopted this generic term in the 16th century, but by the end of the 19th century, “bambara” was used to refer more specifically to the sedentary non-Muslim inhabitants of what is now central Mali3. Today, “bambara” has been supplanted by the term “bamana”, which comes closer to the name given to itself by this people, almost totally converted to Islam.

______

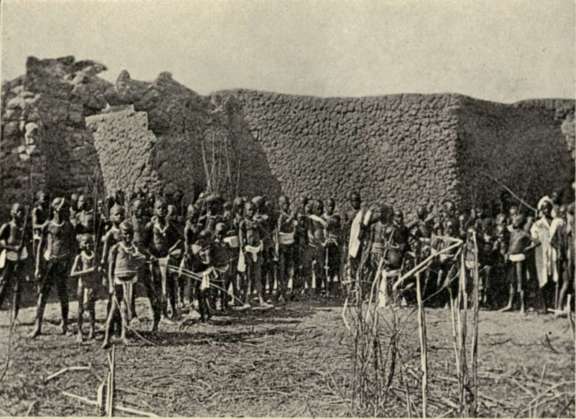

The principal masks of male initiation societies

In the past, the Bamanaya educational systems principally involved two professional groups: farmers/hunters and blacksmiths. Through the play of alliances and influence, the latter contributed to diffusing and controlling these male schools of social, religious, political, legal and esoteric knowledge. The blacksmiths were in charge of the most powerful initiation societies and also held the exclusive right to make woodcarvings, including masks.

Pedagogical aids for candidates, the masks accessible to boys and young adults, such as the N'tomo, the Korè and the Ci wara, appeared not only during initiatory seclusion but also during village entertainment.

Different stages, - the number of which could vary from village to village -, enabled access to greater knowledge and power. The most powerful male secret societies, the Komo and the Kono, also required religious materials such as masks and boliw (power objects), which it was forbidden for the uninitiated to see.

But before being admitted to a young adult society, and then to an adult society, any son joining the Bamanaya had to pass through the initiatory antechamber, the N’tomo4.

______

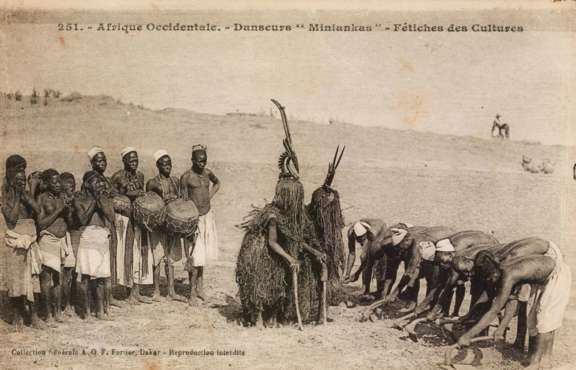

The N'tomo society: mask occasions

N’tomo (or N’domo) means “jujube tree” in Bamana. The term refers to the tree on which the initiation society’s sacrifices were offered. N’tomadyiri (lit.: the N’tomo tree), ancestor of the blacksmiths and creator of the society, is also considered to be “the inventor of the human spirit”. According to oral sources collected by Dominique Zahan, N’tomadyiri was the first to rough-hew the mask and consolidate the rules of the teaching5.

The N’tomo trained uncircumcised boys, between 6 and 13 years of age. Before joining the institution, the young candidates, known as n’tomo dew, chose a girl of their own age, their n’golo muso, with whom a special friendly relationship was established. The n’golo muso followed the transformation of the n’tomo de (pl. dew) and prepared his meals for the annual N’tomo festival, while the n’tomo de undertook to watch over her and give her gifts.

Although the elders gave advice and instruction to the boys, they did not directly intervene in the closed and secret initiation area, as no circumcised persons were admitted there. A chief was appointed among the oldest boys in the year group, assisted by a deputy and two assistants. They then designated the wearer of the N’tomo ku mask (lit.: N’tomo head).

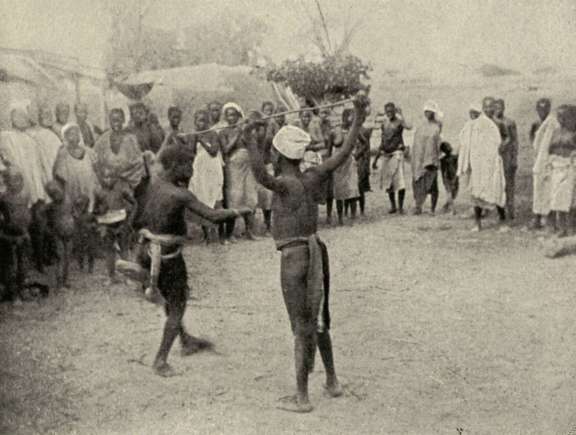

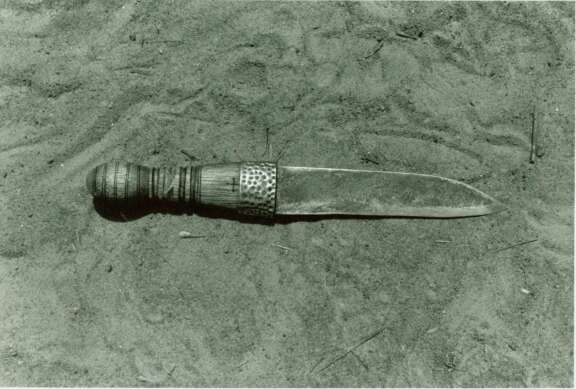

Each year group received between three and five years of training, subdivided into grades. Depending on the locality, each of these classes had its own emblems and animal names, such as lion, toad or guinea fowl6. The teaching dealt with metaphysical questions (death, life, religion, the creation of the human spirit)7, self-control and man’s place in a society that valued solidarity, humility and respect for the elders. These theoretical teachings were coupled with tests to be completed collectively: providing food for the period of initiatory seclusion by collecting alms and agricultural work, hunting and fishing. Physical tests also awaited the young candidates. They took place during the annual festival, after the harvest, usually in December at the time of the solstice8. In the secrecy of the initiatory space, the candidates faced each other in flogging duels using a “branch of nyuanyua9 or sambe”10 provided for the occasion. Like the mask, inseparable from the whip made from one of these tree species, the child controlled the sounds of his voice and the expression of his pain, as the flogging went so far as to draw blood. The mask was present, also inflicting blows on their legs and arms. On this secret occasion, and only at this time, the initiates could take turns wearing the mask.

N'tomo ku, N'tomo mask performances, were held in the initiatory enclosure reserved for education of the initiates, during its annual dry season festival. In the days and weeks preceding the ceremony, initiates visited millet threshing floors, crossroads and the villagers for ritual alms collections. Two choreographies have been recorded: the first, known as téré, was danced on the millet threshing floor, where the mask mimicked coitus, and the second, N’tomo do, was accompanied by songs that “compare the human spirit to the beauty of flowers”11. Today it principally appears at the opening of sogow festivals, where mask and puppet performances are held for the purpose of entertainment.

______

11 Ibidem, pp. 99 and109.

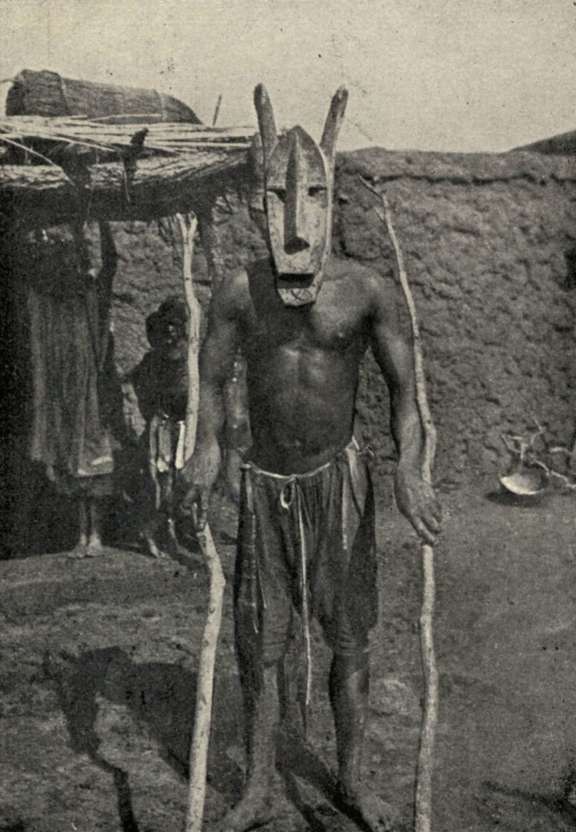

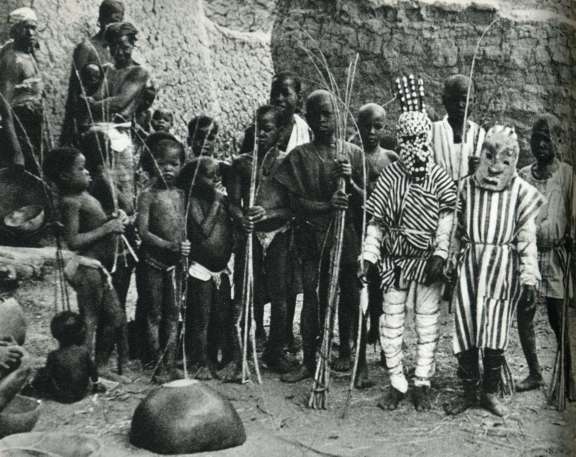

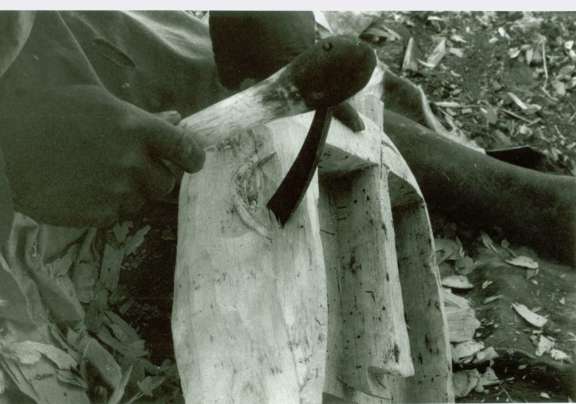

The morphology of the masks

The N’tomo mask bears no resemblance to any known thing, it is a kind of “clawed and horned being, which it is forbidden to define”12. The wearer, always armed with a whip, covers his face with a sculpted mask and covers his entire body with the dloki13 garment, consisting of a cotton blouse and trousers; the feet, hands and back of the head are also covered. In its general morphology, the mouth, which is unobtrusive or even absent on the oldest masks, contrasts with the prominent nose. Wooden face masks bearing three or six horns belonged to the male gender, and those with a comb of four or eight horns belonged to the female gender; two, five or seven horns enabled the identification of androgynous masks14. The N’tomo masks in the Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière donation therefore belong to the female gender and, according to Dominique Zahan, their four horns reveal “man’s corporeal nature, his femininity, passivity and suffering”15.

One of the two masks in the donation has two sculpted antelope horns associated with two “long, upright pointed ears adorned with red cotton, a sign of attention and vigilance”16. The slender, very finely carved horns might recall those of the Ci wara agricultural society’s antelope masks. The comb, with its animal-like appearance, surmounts a face whose curves and eyes are reminiscent of those of a hyena, in a stylisation characteristic of the masks of the Korè society of circumcised young men, as “in many villages the n’domo ku is known as the “n’domo hyena”, n’domo suruku.”17

This ancient N’tomo mask combines iconographic elements from several societies; by extension it heralds the boys’ metamorphoses as a result of rigorous training. The sculptor also created harmonious lines in the curve of the face, adorning it with zig-zag motifs and, in the same block of wood, a human head protruding from the forehead. Wearing a women’s nasal ornament, it could represent Nyeleni, “the little Nyele”, “a symbol of the ideal woman to whom boys aspire after their circumcision and initiation”18, a figure that constitutes the central image of the Jo mixed initiation society.

The other mask in the donation has a female figure standing on its head. Her disproportionate hands, spindly neck, short legs and aquiline nose are comparable with two other sculptures conserved at the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac. The latter, as well as another N’tomo mask surmounted by a crocodile, come from the region around the town of Ségou, which could also be the place of origin of the N’tomo mask in the Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière donation.

______

The Sculptor

Numuw blacksmiths hold a monopoly on woodcarving. Like other materials, this material is held to contain a dangerous energy known as nyama. Blacksmiths alone have the knowledge and power to master it, which is why it is also called nyamakalaw. Wood-working Numuw specialize in this field, and some of them have reputations such that members of ton (associations of young adults) or initiation societies are led to travel miles in order to come and order masks, puppets, statuary or even wooden locks from them.

Depending on the sculpture to be made, and before any tree felling, the blacksmith communicates with a djinn spirit in order to learn the precise location and the appropriate size, shape and tree species19. This may be done several months or even several years after the wood has been cut20. For protection against the wood nyama, the sculptor’s tools - adzes, chisels and knives - receive sacrificial offerings once a year21.

The blacksmith-sculptor works far from view, usually in the bush, protecting himself from danger by taking medicines and complying with prohibitions such as sexual abstinence22. The nyamakalaw sculptor’s skill enables the concentration of spiritual power in the work’s form. This power is the object’s primary quality, forcing its creator to move aside and make way for it, becoming anonymous.

Dominique Zahan lists three possible tree species for the sculpting of N’tomo masks: m’peku (Lannea acida), goni (Pterocarpus africanus) and balanzan (Acacia albida). However, preference tended to be given to m’peku wood, used for the very first mask invented by N’tomodyiri23. Maintenance and conservation of the mask was then left to the object’s owners. Within the framework of N’tomo, the persons in charge would coat the wood with shea butter or fat at the beginning of the dry season for the first annual showings of the mask24.

________

Background of the works

The N’tomo mask with a hyena face, which has no known equivalent, was acquired by the collector and dealer René Rasmussen. The former bookseller and publisher René Rasmussen (1912-1979), who was close to Tristan Tzara and André Breton25, principally collected modern art (Yves Klein, Roberto Matta, Hans Bellmer, André Lanskoy, Karel Appel and Georges Matthieu26) and African art, as from the immediate post-war period. In 1959, with his wife and his friend Robert Duperrier, he opened his gallery of African art A.A.A at 1 rue de l’Abbaye in Paris. Before the African countries’ independence his principal suppliers of objects were colonials, as well as researchers such as François di Dio. After 1960 they were replaced by African antiques dealers and French people returning from Africa27.

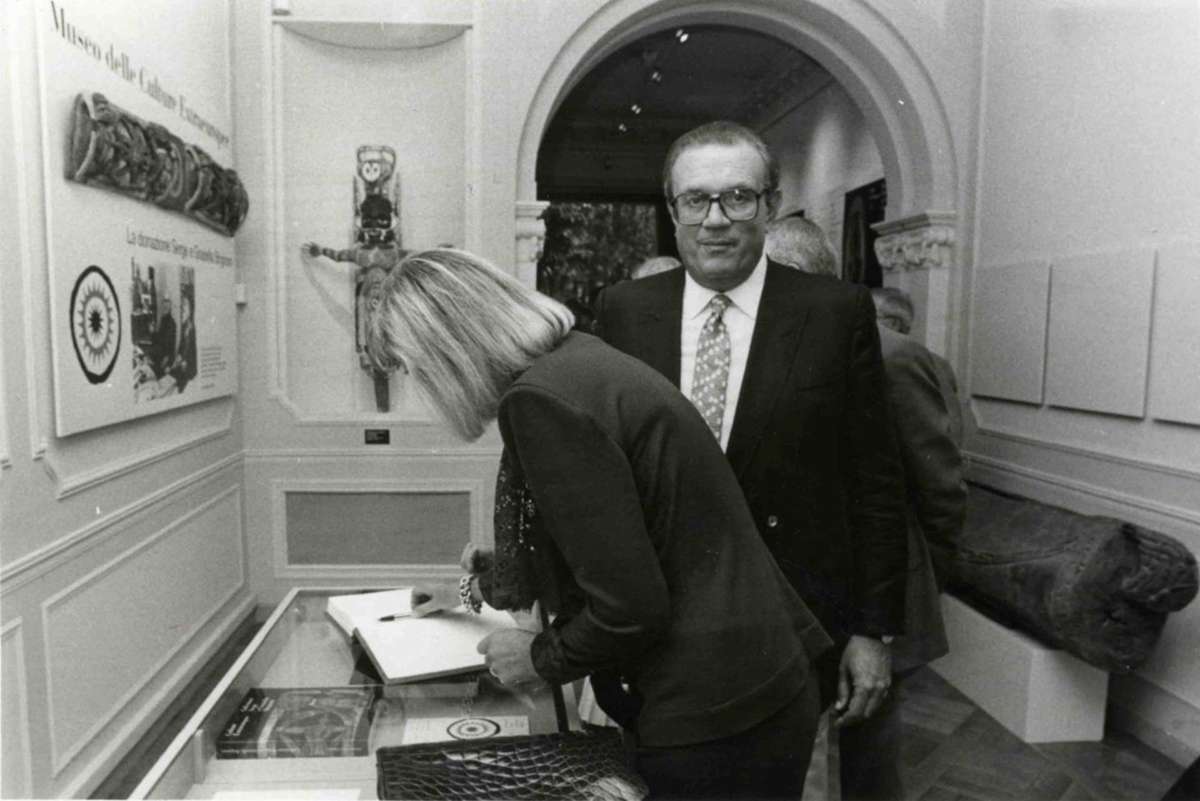

The mask surmounted by a female figure was first acquired by the Swiss collector and art dealer Georges F. Keller (1899-1981). Born in Paris, George F. Keller began his career as a modern art dealer in the French capital in the 1920s and then in New York in the 1930s. In Philadelphia, he advised the famous American collector Albert C. Barnes. He exhibited and sold works in his gallery by certain School of Paris artists and Surrealists, such as Salvador Dali, at the same time building up his own modern art collection. In 1951, he deposited the collection in the Museum of Fine Arts Bern (Kunstmuseum Bern), to which he bequeathed it in 1981. From the 1950s, his collection focused almost exclusively on African art, about which he developed a passion at the age of 19, becoming one of the most important collections in the West28. In 1980, once again at the Museum of Fine Arts Bern, Keller presented three hundred and nineteen objects from his collection of African art and sixteen objects of Oceanic art. He entrusted Paolo Morigi with drafting the catalogue of Raccolta di un amatore d’arte primitiva, in which this mask was exhibited.

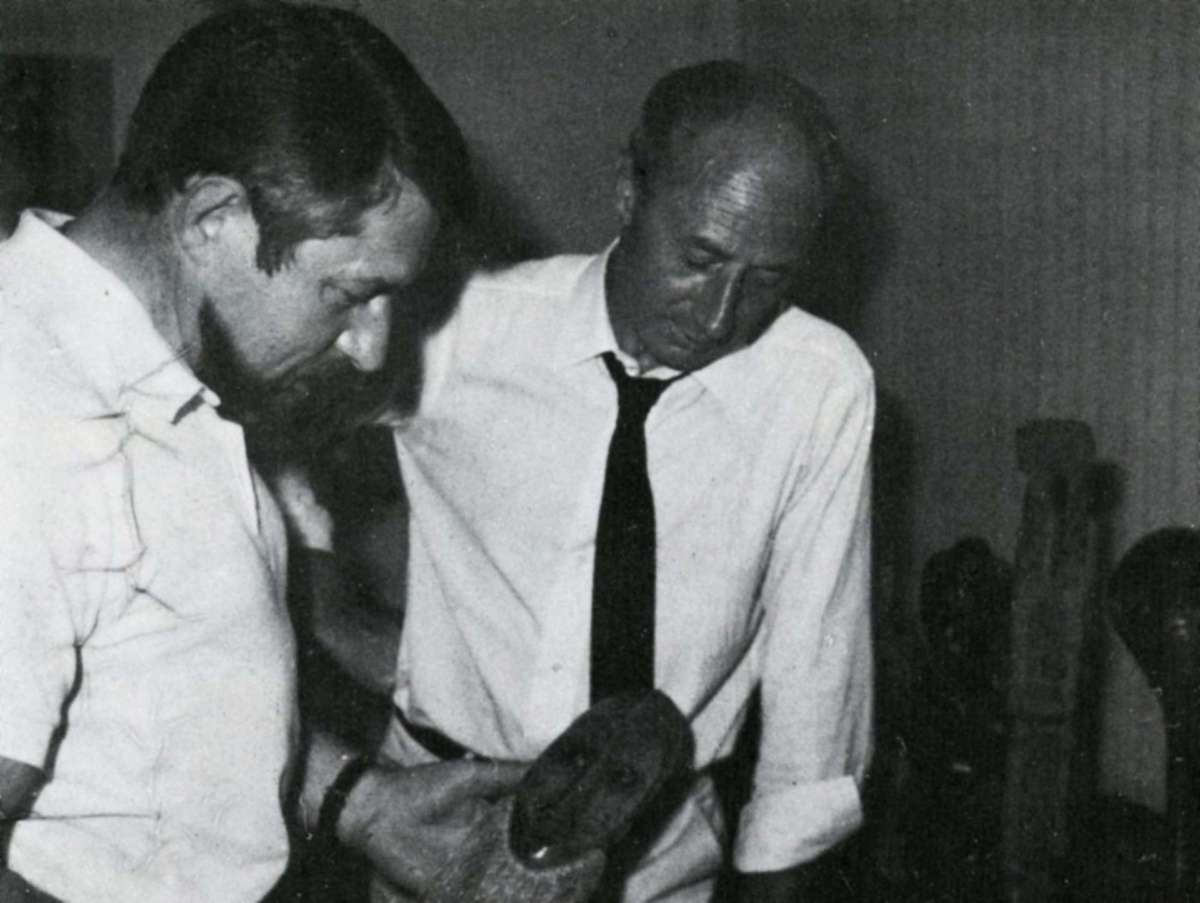

After Georges F. Keller’s death, the mask joined the collection of his friend Paolo Morigi (1939 - 2017), a Swiss citizen of Italian origin. Morigi, a collector of African art, gallery owner and independent researcher, constantly enriched his knowledge of West Africa, making frequent on-site visits to gather information on the objects, and on Ivorian and Liberian cultures in particular, and building up extensive photographic documentation. He was also an academician at the Burckhardt Academy in Rome.

______

Selective biography and cartography

Maps

Thierry Renard (2020), musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Paris.

Publications

Bazin, Jean “Bambara” in Mali Kow, exhibition catalogue, Montpellier: Indigène ed., 2001.

Bazin, Jean “À chacun son Bambara” in Amselle, Jean-Loup and M’Bokolo, Elikia (eds.), Au cœur de l’ethnie. Paris: La découverte, 2009, pp. 87-126. [First edition: 1989]

Colleyn, Jean-Paul “Bamanaya – Un art de vivre au Mali” in Bamanaya. Milano: Centro Studi Archeologia Africana, 1998.

Colleyn, Jean-Paul (ed.), Bamana – un art et un savoir-vivre au Mali. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2002.

Colleyn, Jean-Paul, Bamana, Milan: 5 Continents, Visions of Africa collection, 2009.

COLLEYN, Jean-Paul, « Tenir sa bouche », Terrain [Online], 72, p. 188 | November 2019, URL : http://journals.openedition.org/terrain/19206 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/terrain.19206

BRETT-SMITH, Sarah C., The Making of Bamana Sculpture: Creativity and Gender. Cambridge New York : Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Henry, Joseph L’âme d'un peuple africain: les Bambara, leur vie psychique, éthique, sociale, religieuse. Münster i. W.: Aschendorff, 1910.

JOUBERT, Hélène, Éclectique : une collection du XXIe siècle. Paris : musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, 2016.

Lehuard, Raoul, “La collection Rasmussen vendue par Me Libert” in Arts d’Afrique Noire, Winter 1979, no. 32, pp. 21–25.

Monteil, Charles, Les Bambara du Segou et du Kaarta: étude historique, ethnographique et littéraire d'une peuplade du Soudan français. Paris: E. Larose, 1927. New edition of 1977.

Morigi, Paolo, Raccolta di un amatore d’arte primitiva. Bern: Kunstmuseum, 1980.

Pageard, Robert, “Plantes à brûler chez les Bambara”, Journal de la Société des Africanistes, 1967, volume 37, fascicle 1. pp. 87-130.

Valluet, Christine, Collectors’ Visions. Milan: 5 Continents, 2018.

ZAHAN, Dominique, Sociétés d'initiation bambara : le n'domo, le ko̧ rè. Paris La Haye: Mouton, 1960.

Auction catalogue

Sotheby’s, Paris, Paolo Morigi collection (2nd part), 6th December 2005.